Problem

Assessing floating matter drift in the ocean is of importance for a number of key reasons. These range from improving search-and-rescue operations at sea; to better understanding the drift of flotsam of different nature including macroalgae such as Sargassum, airplane wreckage, tsunami debris, sea-ice pieces, larvae, and oil; to better interpreting ‘Lagrangian’ observations in the ocean. At present, largely piecemeal, ad-hoc approaches are taken to simulate the effects of ocean currents and winds on the drift of floating objects. A systematic approach ideally founded on first principles is needed.

Development

Our group has been seeking a systematic approach by building on the Maxey–Riley set, the de-jure framework for the study of finites-size, buoyant or inertial particle dynamics in fluid mechanics. As is well-known in that field, inertial particles cannot instantaneously adjust their velocities to changes in the carrying fluid velocity. Thus their dynamics fundamentally differ from those of fluid or Lagrangian (i.e., infinitesimally small, neutrally buoyant) particles. Solving for the exact motion of inertial particles would involve solving the Navier–Stokes equation with moving boundaries. The Maxey–Riley framework provides an approximate solution to the ensuing highly complicated PDE problem through the resolution of an ODE.

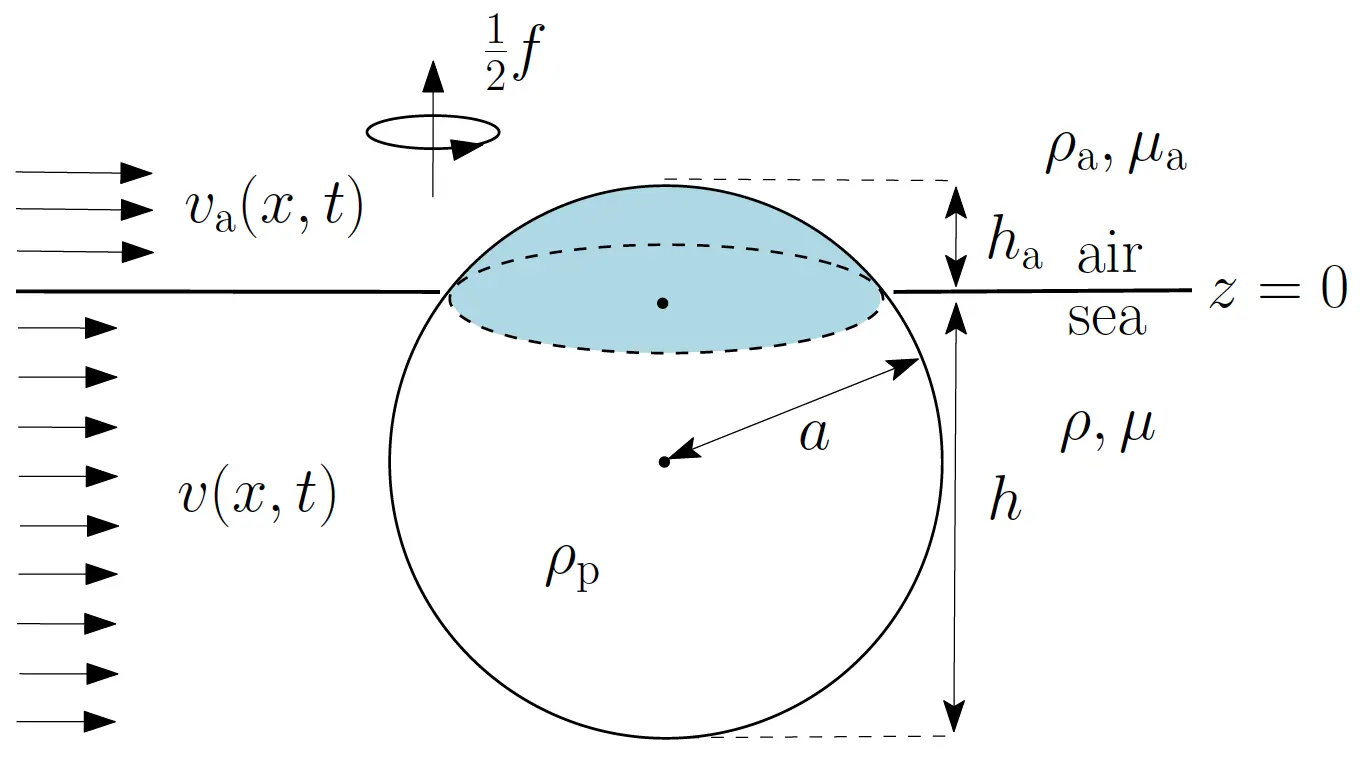

Built on first principles, the Maxey–Riley is a classical mechanics second Newton’s law for the motion of inertial particles immersed in a fluid in motion. We have extended the validity of Maxey–Riley set to finite-size particles that float at the air–sea interface accounting for the combined effects of ocean currents v(x,t) and wind drags va(x,t). Investigating inertial dynamics on the slow manifold, a codimension-two manifold that attracts all solutions of the Maxey–Riley set, has enabled us to gain important insight. This includes the possible role of mesoscale eddies as attractors of flotsam or the tendency of the latter to develop large patches in the centers of the subtropical gyres.

Validation

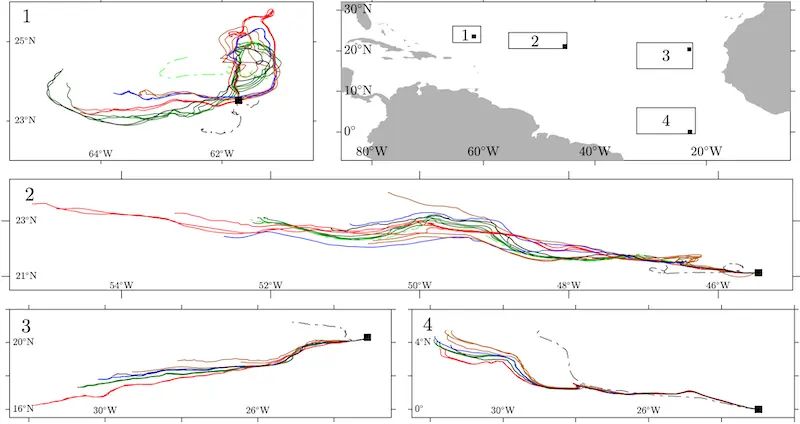

First, a series of field experiments were carried in the Atlantic Ocean, in collaboration with researcher from NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Special buoys with different inertial characteristics (size, shape, and buoyancy) were deployed simultaneously to observe the effects of inertia of the objects’ trajectories (see Olascoaga et al., 2020 and Miron et al., 2020b) and to test the Beron-Vera-Olascoaga-Miron (BOM) framework.

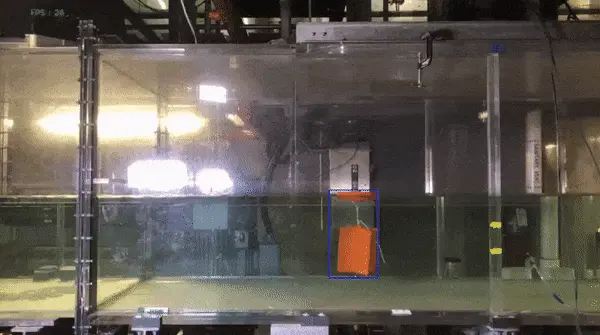

Second, laboratory measurements were carried out in a controlled environment in the wave-tank facility at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. The objects (a smaller CARTHE drifter replica and four spheres of different buoyancy) were released in the funnel and recorded as they traveled downstream. Each object was later tracked to quantify the effect of the wind and the current on its velocity and to compare with the theoretical values from the BOM framework (Miron et al. 2020a).

Publications

- P. Miron, M.J. Olascoaga, F.J. Beron-Vera, N.F. Putman, J. Triñanes, R. Lumpkin and G.J. Goni, How local winds and currents impact the trajectories of marine debris and Sargassum: Inertia-dependent clustering of floating material paths, Preprint, 2020b

- P. Miron, S. Medina, M.J. Olascoaga and F.J. Beron-Vera, Laboratory verification of the buoyancy dependence of the carrying flow in a Maxey–Riley theory for inertial ocean dynamics, Preprint, 2020a

- M.J. Olascoaga, F.J. Beron-Vera, and P. Miron, Observation and quantification of inertial effects on the drift of floating objects at the ocean surface, Physics of Fluid, 2020, link

- F. J. Beron-Vera, M. J. Olascoaga and P. Miron, Building a Maxey–Riley framework for surface ocean inertial, Physics of Fluids, 2019, link